Choosy

'Abortion reversal' has made it from America to Aotearoa. We should be worried. Please be aware that challenging content follows.

There’s a prequel to this story of choice.

There were a bunch of us, my mates and I, from big families who were scrubbed and combed and herded to Mass on a Sunday; holdouts in a secular world, even though it was now the 80s and 90s. We sat through religious education classes together, Monday to Friday, learning about the sanctity of marriage, the sacredness of life - before getting drunk in garages in the weekends, same as the kids from the state schools.

By that time, some of the tenets of our faith had become a tough sell. A second wave of feminism, thriving in the same era our mothers conceived us, insisted girls and women should have choice. Choice. Even among the most traditional of the men in frocks, the idea that blokes should do the thinking for women was becoming hard to defend.

That system never worked so well anyway. By the time Gen X girls were old enough to roll our eyes at it, we’d figured out certain stuff, including that some of our mums were already knocked up when they’d married our dads. Our elders’ failure to practise what they preached didn’t stop the preaching, mind you - and we carried this stuff on in a strange kind of shared fiction.

But if trying to take away their choice wasn’t enough to control our mothers, it probably wouldn’t work on us. There was nothing else for it. In these modern times, the definition of ‘choice’ itself needed to change. Let me explain to you how this works.

When I expressed teenage annoyance one time that women are barred from the priesthood, a man from my church explained the only women who complain about that stuff don’t want to be priests anyway. It was a neat little trick, the same catch-22 the traditional apply to every issue of women’s autonomy. Any ordinary woman has choice, but the right-minded woman doesn’t need choice. She already knows the correct thing to do. And relinquishing your choice is still a choice, isn’t it?

God is more pragmatic than you’d think. He’ll look away from sex, especially when the clergy are doing it, and greed and venality and drinking, and the mysterious movements of money that smooth over misdemeanours. But there’s one sin on which He will not budge. I had that choice, yes, but it never really felt like a choice.

Maybe that’s why the Ministry of Health media release caught my attention - mine but almost no one else’s, except for an organisation called Family Life International NZ. The media release was titled, unemotively, Ministry warns against the use of progesterone for ‘abortion reversal’.1

And what is abortion reversal? It’s a known hoax, a travesty, and a grave threat to health - especially the health of girls and women.

But its promise?

Well, it offers to undo that choice you only thought you wanted, because you didn’t know any better.

This story gnaws at me. We will soon meet its characters, both here and overseas, and explore the uncomfortable turns of its plot. Before we do, we need to set the scene. Until 2020, when the previous Labour government overhauled our abortion laws, a workaround - one based on a strange shared fiction - prevailed. To understand abortion reversal we need to go back a little, looking at abortion law, how abortions are provided, and how these things have combined to change the choices available to pregnant people.

Before 2020, a lot of the rules around abortion were set out in the Crimes Act 1961.2 Abortion was unlawful except in certain situations, allowing us to believe it both was and wasn’t accessible, whatever we preferred. The way the Act described those situations is jarring - but I quote it purposely to give you a sense of the attitudes behind the legislation. The situations in which abortion wasn’t unlawful were these:

a) that the continuance of the pregnancy would result in serious danger (not being danger normally attendant upon childbirth) to the life, or to the physical or mental health, of the woman or girl; or

(aa) that there is a substantial risk that the child, if born, would be so physically or mentally abnormal as to be seriously handicapped; or

(b) that the pregnancy is the result of sexual intercourse between—

(i) a parent and child; or

(ii) a brother and sister, whether of the whole blood or of the half blood; or

(iii) a grandparent and grandchild; or

(c) that the pregnancy is the result of sexual intercourse that constitutes an offence against section 131(1); or

(d) that the woman or girl is severely subnormal within the meaning of section 138(2).

Although not in themselves grounds for abortion, these factors could also be taken into account:

a) the age of the woman or girl concerned is near the beginning or the end of the usual child-bearing years:

b) the fact (where such is the case) that there are reasonable grounds for believing that the pregnancy is the result of sexual violation.

After 20 weeks’ pregnancy, the rules under the Crimes Act got even more stringent, with abortion lawful only when ‘necessary to save the life of the woman or girl or to prevent serious permanent injury to her physical or mental health’.

The Crimes Act forced most people seeking abortions to be untruthful, claiming severe danger to their mental health - the grounds for about 98% to 99% of abortions.3 But, leaving aside that people shouldn’t have to lie to get healthcare, did this workaround make abortion accessible? Was our strange shared fiction not so bad?

In practise, the old system created a lot of hoops to jump through. As well as meeting the circumstances in the Crimes Act, a person had to see not one but two ‘certifying consultants’ to get an abortion. They might be required to get pre-abortion counselling too.

Why did the hoops matter? For a bunch of reasons - but one is that when someone needs an abortion, their choices are affected by timeframes. The earlier you can make your choice, the more options are available to you, and the safer your abortion is likely to be.4 In the first 9-10 weeks, you may be able to have what is called an ‘early medical abortion’. We’ll come back to what this means soon.

The 2020 overhaul took abortion, along with the awful wording we’ve just seen, out of the Crimes Act, making it the Ministry of Health’s responsibility. The hoops involving certifying consultants and pre-abortion counselling were scrapped. Now a person could refer themselves directly to a provider and, if under 20 weeks pregnant, simply get an abortion in most situations. Abortions at over 20 weeks became for clinicians to decide, not the law. The upshot? People needing abortions are now more likely to access an early medical abortion - rather than a later abortion with a different method, such as surgical abortion.5

The how of an early medical abortion is important, if we’re going to understand abortion reversal - so we’ll touch on it now.

An early medical abortion can happen at home, and can sometimes even be arranged by phone. It requires a pregnant person to take two pills. The first pill is something called mifepristone. It blocks the hormone progesterone, which is needed for a pregnancy to continue. The second pill is called misoprostol. This causes the uterus to contract so the pregnancy tissue leaves the body, like a miscarriage. The two pills are meant to be taken 24 to 48 hours apart.6 After taking the second pill, the bleeding that will end the pregnancy begins within hours.

OK, you can see how a law change plus early medical abortion have increased choice, especially for girls and women. Turns out that’s not a development that everyone’s comfortable with.

Let’s now talk about abortion reversals. We saw how mifepristone, the first pill taken during an early medical abortion, blocks the progesterone needed to continue a pregnancy. If the pregnant person changes their mind about an abortion before they take the second pill, the misoprostol that removes the pregnancy from the body, then the abortion can be stopped. All they need is a top-up dose of the progesterone that the first pill blocked, right?

Right?

It turns out science is actually trickier than that. Who knew?

Predictably, the story of abortion reversal - so much about girls and women - started with a man. His name is George Delgado, and he lives in San Diego. He’s a medical doctor and a researcher, although he seems unbothered with the normal standards of either profession. The science behind abortion reversal, such as it is, mostly comes from him. We’ll spend a moment looking at that science to understand just how ropy it is, and how misrepresented it’s been.

A paltry three studies are relied on to support abortion reversals: two by George Delgado, and a third that was just as bad and even smaller.7 All three studies are what are called ‘case series’, which really just means observing the cases of a bunch of individuals.8 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, in describing abortion reversal as ‘unproven and unethical’, describe case series as the weakest form of evidence, partly because there’s no control group.9 Without a control group, or people not getting the ‘treatment’ to compare against, you can’t know whether the thing that’s happening to the people you’re studying - in this case, continued pregnancy - is actually caused by that ‘treatment’. Notwithstanding, George claims abortion reversal has 64 to 68 percent success - a rate that experts have accused him of inflating by only giving progesterone to those who remained pregnant after the mifepristone (making them more likely to carry a pregnancy to term, regardless of progesterone).10

A case series or three, even if done well, simply isn’t suitable to show a medical treatment is safe - there needs to be a clinical trial. And yet if that was the worst George Delgado had done, maybe we wouldn’t be here. The technical term for his case series methodology is a ‘dog’s breakfast’. His first study wasn’t supervised by an ethical review committee or other suitable body - a requirement for research with human subjects. Subsequent case series were no better, lacking ethics approval and a control group, not reporting properly (a bunch of patients simply dropped out of his data), and failing to record patient safety outcomes.11 It’s the kind of stuff that, if it happened in Aotearoa, would end a person’s career in disgrace.

In 2019, a researcher named Mitchell Creinin - sceptical of abortion reversal, and concerned to see it given legitimacy in states’ legislation - set out to test Delgado’s shonky conclusions with a reputable study.12 He established a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial (a research approach that involves a control group and lots of other safeguards against errors and researcher bias). The plan was to study 40 patients who were early in pregnancy and intended to have surgical abortions. Before they reached the point of surgical abortion, patients were given mifepristone, the first of the two pills involved in an early medical abortion - followed either by progesterone, which is meant to bring about an abortion reversal, or by a placebo. Either way, progesterone or placebo, their medical abortion was left incomplete.

If Creinin’s trial had shown abortion reversal to have no effect, that would have been bad enough. In 2020, after three patients haemorrhaged so severely they were taken to hospital by ambulance, the trial was called off midway in the interests of safety. Only 12 patients had taken part.13

Creinin said, "It's not that medical abortion is dangerous. It's not completing the regimen, and encouraging women, leading them to believe that not finishing the regimen is safe. That's really dangerous."14

And the kicker is this. Another reputable study from 2015 found that after mifepristone is taken, the chances of staying pregnant are much this same, with or without progesterone.15 As best we know, folks who risk abortion reversal - who are told it’s safe by people who don’t even flinch when they lie - risk their health, maybe their lives, for nothing.

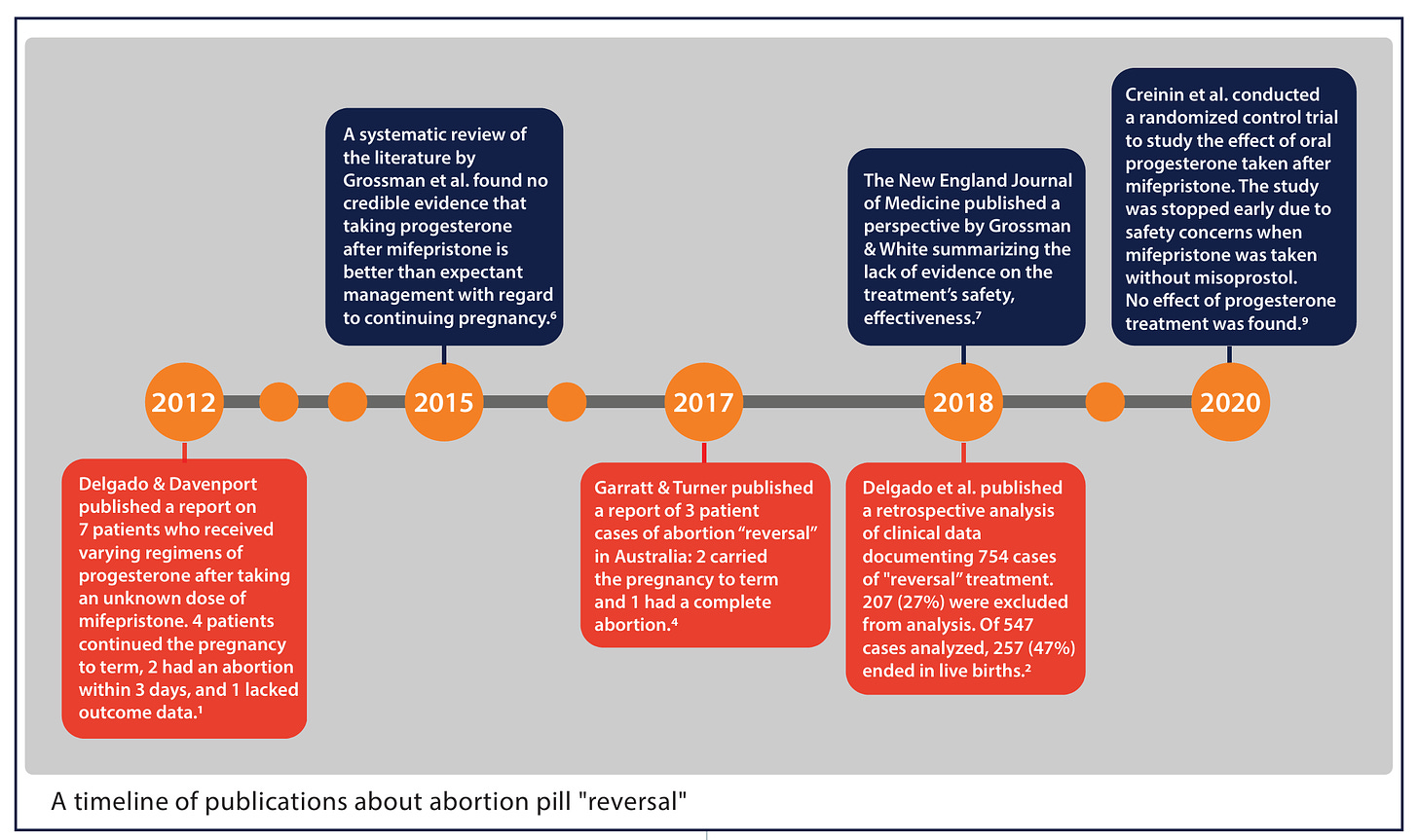

[Picture credit: A timeline summarising the science behind abortion reversal, with the real science above and the crappy science below. Taken from a July 2020 issue brief by Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health.]

We’ve met George Delgado, but have we really met George Delgado?

In his telling - and George likes to tell it a lot, to anyone who’ll listen - he’s in it for us, the women.16 There was a time, and I grew up in it, when the anti-abortion movement mostly used a different language. They would send pamphlets to my house, with fake pictures of dismembered fetuses who’d screamed as they died; stories of hateful, selfish women who tried to kill their babies, and the heroic people who’d do anything to stop them.

But that was then. Now, as we’re going to see, it’s about women’s choice.

Today, George is the director of something called Culture of Life Family Services. The California facility offers “Christ-centered medical care” and, for the avoidance of doubt about what that means, displays renditions of Jesus on the cross, the Last Supper and Mother Teresa.17 Amongst its services, the facility offers an ‘abortion pill rescue’ to help women stuck in the kind of indecision only caps lock can cut through:

We know that an unplanned pregnancy can be scary and many women make impulse decisions. We know that after thinking about it, many women would like to change their minds about a MEDICATION ABORTION.18

George’s narrative begins with an experience that wasn’t his own. Fifteen years ago, a Texan woman commenced a medical abortion, taking mifepristone. After she took it, she felt regret, and she did not take the second pill, the misoprostol. She searched online, and made contact with an anti-abortion activist who in turn contacted George. In George’s retelling, he said ‘I’ve never heard of anybody reversing mifepristone. Let me think about it.’ It was then the Holy Spirit showed up. True story.

The Holy Spirit must have reassured George, who is qualified in family medicine and palliative care, that it was OK to practise outside the scope of his training - because what happened next guided George to the development of abortion reversal. Following what he understood to be a directive from God, George began searching for Texan physicians who, like him, had been trained in natural family planning by a Catholic organisation opposed to contraception. He found one willing to try out his idea; and the physician gave the pregnant woman progesterone injections for the duration of her pregnancy. Months later, the woman gave birth to a daughter.

George’s idea flourished, and he went on to found the Abortion Pill Rescue Network, which describes itself with the slogan ‘a last chance to choose life’, because ‘no woman should ever feel forced to finish an abortion she regrets’. The Network claims to have helped women right across America and in 93 other countries - coyly declining to name those countries, perhaps because of the questionable lawfulness of its activities in some of them.19 In 2017, George partnered with an organisation called Heartbeat International, who agreed to take over the running of the Network.20 We haven’t heard the last of Heartbeat International.

Even by the standards of the anti-abortion movement, George holds unusual beliefs. At an event this year, he claimed with a shocking crassness that “This is life versus death, much more fundamental to our existence and to our relationship with our creator than being free or being a slave,” and warned of the potential for civil war. His view that fetuses are people extends to frozen embryos stored in labs - which he suggests should be baptised, even though it would destroy them, to give them a ‘course to salvation’.21

But the strangeness of the fictions George peddles hasn’t stopped others from sharing them - or sometimes embedding them in the law. Presumably thanks to some further prompting by the Holy Spirit, George is also a lobbyist. He doesn’t always win, but he’s pretty damn good.

In June, George and a group of fellow plaintiffs (calling themselves the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine) lost their legal bid to have mifepristone banned on the grounds it’s unsafe for women, with negative impacts for the doctors who care for the women. George - and I don’t know whether to laugh or cry - also argued, “When my patients have chemical abortions, there is a tangible financial loss to my practice in losing the opportunity to render professional prenatal care for the mother or to care for babies who are never born.”22 God loves a trier, I guess - but in a refreshing moment of not being idiots, the Supreme Court sent George and his pals packing.23

But George isn’t done, not even. The next battle he’s waging involves not mifepristone, but this time abortion reversal. It’s a fight that’s been brewing for a while. As we speak, a bunch of states are considering legislation that would require abortion clinics to tell people that abortions can be reversed. One such law has already passed in Kansas, although it’s been put on hold. In the other direction, Colorada has become the first state to ban abortion reversals - although the ban is currently being challenged by anti-abortion protestors, who argue nuttily it impinges on the rights to free speech and religious freedom of abortion reversal prescribers.24 Meanwhile, California has filed a lawsuit against Heartbeat International for “fraudulent and misleading claims to advertise an unproven and largely experimental procedure.” And who’s counter-suing the California Attorney General? Bless: it’s George’s Culture of Life Family Services.25

Still, all George is doing is looking out for girls and women, our right to choose. As he puts it:

Oftentimes, these women, they have almost immediate misgivings about taking the abortion pill. There is a window of opportunity for women who change their mind and want a second chance at choice. You would think that these people who call themself pro-choice would support a woman’s second chance at choice.

Regret.

It’s the other side of the coin that is choice - the weaponised reminder that these days a woman may be free to choose, but that doesn’t mean her choice won’t be punished, even if only by herself. Visit any anti-abortion website, and the symptoms of the regretful women will be much the same: depression, alcoholism, marriage breakdown, career failure, trauma, or feeling ‘dead inside’. Turning back to the research, let’s explore the issue of regret a little further. I’ve been unable to find evidence from Aotearoa, so instead we’ll look at something called the Turnaway study - a landmark piece of research from America.

The Turnaway study is what’s called a longitudinal study, following its participants over time. One thousand American women were recruited, some of whom had gotten abortions, and some of whom wanted abortions but were turned down (the so-called turnaways). Turnaway set out to challenge the weaknesses of previous abortion studies, which compared women who’d had abortions with women who’d continued their pregnancies by choice - a flawed comparison, because these women are in different circumstances. Turnaway’s findings? Well, they’re kind of remarkable.

The women who had abortions were no more likely to experience anxiety, depression or suicidal ideation than the ones who were turned down.

The women who were turned down had a four-times-greater chance of living below the poverty line, as well as being more likely to get stuck in abusive relationships, have pregnancy-related complications or experience poor health.

And regrets? Five years after their abortion, 95% of women in the study who’d had abortions reported it was the right decision.26

Regret amongst people who’ve had abortions is uncommon. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen, or it shouldn’t matter when it does. It surprised me a little to learn that the woman whose anguished choice launched abortion reversal, and George Delgado’s career, is real.

Fifteen years ago, Erin Medina was terrified as she drove to a Texas Planned Parenting clinic for an abortion. She was single, she was unemployed, and she had a four-year-old boy already. With another baby, she couldn’t imagine how she’d survive. Erin took the first pill, the mifepristone, but straight away she felt it wasn’t right - and so she turned to her frantic internet search. As she said later, she’d been thinking about abortion because she had no support system. The year before she got pregnant again, she’d ‘received Christ’. She has not courted the limelight since her choice to have her daughter. Years on, she says of abortion reversal, “I don’t know the intricate medical stuff. But you have to believe in a higher power.”27

I don’t want to make out Erin is some kind of puppet or dupe. To me, she seems brave. Choice is as complex as it’s personal, just like faith or regret or a hundred other things that humans feel or do. But I do know that any choice is made within a context. And I have a few insights from my own experience as a daunted girl who grew into a questioning woman.

Autonomy is ebbed away more than it is wrenched or yanked.

You can be told any ordinary woman has choice, but the right-minded woman doesn’t need choice. She already knows the correct thing to do. You wish you could become that kind of woman, worthy of respect; not stay something lesser, like a scatterbrained girl who dreams of a trivial life, making her small-minded choices between career and clothes and holidays. And so you start to wonder: what is it about me, what flaw, that desires a choice over her body? Not to do with it what is fun - everyone does that - but to imagine, selfishly, a fun without repercussion? You think, does that desire come from a failure of my maturity, my morality or my mind? Is it better, maybe, if I don’t do the choosing - relinquishing it to someone who knows better? After all, a person can’t regret a choice they never let themselves make.

If you are like me, or like I was, grappling with strange fictions that a part of you wanted to share, then you’ve tied yourself in so many knots you hardly trusted your judgement at all.

You might have wondered something, if you’ve read this far. Given abortion reversal makes pregnancies no more likely to continue than doing nothing after taking mifepristone, why does the anti-abortion movement push it so aggressively?

I think of Erin, of any pregnant person like her, searching in that moment of anguish. I see a little of her in myself.

The person who cannot trust their judgement is in their most vulnerable moment - bodily, mentally, spiritually. And there are some who can’t walk past a moment of vulnerability without seeing an opportunity for manipulation.

It’s another neat little trick.

So far, so America - mostly. I have told you tales from a country different to our own, if not as different as we might like to believe. Should we worry? I think we should - and for two reasons I want to explain.

The first reason is that the kinds of organisations with which George Delgado is affiliated, and through which his dangerous fakery is pushed, are networked with others internationally. Let’s circle back to remind ourselves how we began - with a media release by the Ministry of Health, seemingly noticed only by me and an organisation called Family Life International NZ.

Family Life International NZ, whose slogan is ‘Defending life, faith and family’, came out swinging in response to the Ministry of Health. In its own media release titled Ministry of Health refuse pregnant mothers the chance to reverse chemical abortion, drawing again on the language of choice, Family Life International NZ cites both George Delgado and Heartbeat International. When you go to the website of Heartbeat International - which claims to offer abortion reversal in America, as well as 93 other countries it doesn’t name, and is being taken to court for fraudulent and misleading claims - there’s a ‘worldwide directory of pregnancy services’. Type in ‘New Zealand’, and Family Life International NZ and its affiliate helpline, plus one other similar organisation, come up.

But is a relationship between these organisations a problem, if abortion reversal is against the rules here in Aotearoa? This is the second reason we need to worry, and I think it’s more subtle. Let’s step back a bit.

America’s anti-abortion movement is influential, but its moral and intellectual bankruptcy hides in plain sight. George Delgado’s arguments have been widely debunked by reputable research, the media and the legal system. Heartbeat International are being taken to court. The legal system, whether it succeeds or not, is proactively grappling with abortion reversal’s threat.

In Aotearoa, by comparison, abortion reversal is more under the radar. The Ministry of Health set out the expert bodies who’ve denounced it (there are several), the avenues for people to complain about it, and the part of Medicines Act 1981 a person would be breaching if they promoted progesterone for abortion reversal.28 It’s a shot over the bows, and I can make a guess who it’s aimed at - but any action against abortion reversal could well rely on someone coming forward. Someone who’s probably scared, ashamed, feeling alone, or worse - who’s been rushed to hospital haemorrhaging. Maybe someone who was too afraid to go to hospital at all.

Family Life International NZ’s media release talks at length about the availability of progesterone in Aotearoa, and how easily it can be prescribed by a range of medical professionals for any legitimate purpose. At first I understood them to be giving a false reassurance that progesterone is safe when used for abortion reversal. I realised later their words can be also construed another way: progesterone is everywhere. It might just be attainable if you’re really willing to try.

All it takes, after all, is one person unethical enough to source it - and another who’s scared or ashamed or alone enough to say nothing after taking it. That, precisely, is the danger.

Just as this story had a prequel, it also has a coda.

As part of my research, and out of curiosity, I called an information line affiliated with Family Life International NZ. After a few rings, a woman picked up. She was friendly and well-meaning. I could tell from her voice she was older than me: hard to say, but maybe in her fifties or sixties. I said I’d been reading the Family Life International NZ website, and I asked her for information about abortion reversals, including if and how they can be accessed in Aotearoa. She said, just a moment, I’ll get some advice.

When she came back, she read a kind of script to me - or not a script, perhaps, but a print-out of a webpage.

She read aloud about the two pills involved in an early medical abortion, and that progesterone can be taken after the first. Each sentence running on from the next, she continued that progesterone is given to babies to aid their development. It should be given within 24 hours of mifepristone, ideally, but can be taken up to 72 hours. She repeated from the page the phrase ‘abortion-vulnerable women’. She carried on that there are no harmful side effects, and recited a 64 to 68 percent success rate - drawing a direct line from George Delgado’s strange fictions through to the two of us. She finished reading.

How could someone get an abortion reversal, I asked? Check with your GP, she said. She mostly knew about America, she admitted, but there are a few GPs here who’ll prescribe it. But is it safe, I asked? It’s used in normal pregnancies, she replied - and then she added, and abortion isn’t safe anyway.

Was I pregnant, she asked? No, I said. I explained I’d read Ministry of Health information that raised safety concerns. Oh, she said, I don’t know about that, but I’ll have a look. I don’t have any figures on how many women have used progesterone for abortion reversal, she added - before she reiterated, it’s used in normal pregnancies.

I thanked her, she said goodbye kindly enough, and we ended the call.

As I reflected in the hours that followed, I moved between anger and dismay. It was the disinformation, of course; the upbeat brazenness of the lies, the dangerousness of them. But it was more than that. It was the relinquishment our faith teaches women especially. The readiness with which moral agency and critical thinking can be given up in the service of lies. How natural that feels when you’ve been taught to give up agency over your body first.

I used to create a kind of distinction between the likes of George Delgado and the woman on the phone: between the ones who manufacture these strange fictions, and the ones who only share them. I saw a little of myself in the woman, and a small corner of my heart hurt for her - but ultimately, a hurting heart is just a metaphor. A haemorrhage is very real. And you don’t get to look away from the harm you caused because someone else told you to inflict it. Relinquishing your choice is still a damn choice.

And so choice is the thing I come back to. The supposed slam dunk of the anti-abortion movement has always been this: show us the mother who regrets her children. Would I say to my own kids’ faces I deserved to choose not to bear them? Would I want my sons to read what I’ve just written?

I don’t regret my children: they’re my life. But sometimes I look back over that life, at certain of its moments. I wish it was easier to tell what was chosen from what only felt like choice.

Note that pregnant people beyond the 9-10 week mark can also have medical abortions, but they involve stronger drugs, take longer, and need to happen at a hospital or clinic.

Note that anti-abortion activists have made a methodological criticism of Turnaway, that a chunk of the women involved dropped out of the study. This is inevitable in a longitudinal study - people move away, lose interest, change their minds, or even die - but the question becomes whether the remaining group is too small to generate meaningful conclusions. The Turnaway authors have defended their approach, noting that when you’re studying a stigmatised procedure like abortion, drop-out is to be expected. In any case, the authors are reputable, their work has been peer reviewed and published by reputable journals, and they don’t resort to brazenly making stuff up like George Delgado. It’s good enough for me.

Thank you for writing this. That women's right to choose to have an abortion continues to be a battleground (and one dominated by men) makes my head explode. As does the seeming inverse relationship between the attention paid by the likes of George Delgado to the welfare of children before versus after they are born.

Excellent work, Anna. Thank you.